21. Monte Carlo and Option Pricing#

21.1. Overview#

Simple probability calculations can be done either

with pencil and paper, or

by looking up facts about well known probability distributions, or

in our heads.

For example, we can easily work out

the probability of three heads in five flips of a fair coin

the expected value of a random variable that equals \(-10\) with probability \(1/2\) and \(100\) with probability \(1/2\).

But some probability calculations are very complex.

Complex calculations concerning probabilities and expectations occur in many economic and financial problems.

Perhaps the most important tool for handling complicated probability calculations is Monte Carlo methods.

In this lecture we introduce Monte Carlo methods for computing expectations, with some applications in finance.

We will use the following imports.

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from numpy.random import randn

21.2. An introduction to Monte Carlo#

In this section we describe how Monte Carlo can be used to compute expectations.

21.2.3. A vectorized routine#

If we want a more accurate estimate we should increase \(n\).

But the code above runs quite slowly.

To make it faster, let’s implement a vectorized routine using NumPy.

def compute_mean_vectorized(n=1_000_000):

X_1 = np.exp(μ_1 + σ_1 * randn(n))

X_2 = np.exp(μ_2 + σ_2 * randn(n))

X_3 = np.exp(μ_3 + σ_3 * randn(n))

S = (X_1 + X_2 + X_3)**p

return S.mean()

%%time

compute_mean_vectorized()

CPU times: user 80.9 ms, sys: 7 ms, total: 87.9 ms

Wall time: 87.7 ms

np.float64(2.229740241398839)

Notice that this routine is much faster.

We can increase \(n\) to get more accuracy and still have reasonable speed:

%%time

compute_mean_vectorized(n=10_000_000)

CPU times: user 816 ms, sys: 53 ms, total: 869 ms

Wall time: 868 ms

np.float64(2.2297175955362976)

21.3. Pricing a European call option under risk neutrality#

Next we are going to price a European call option under risk neutrality.

Let’s first discuss risk neutrality and then consider European options.

21.3.1. Risk-neutral pricing#

When we use risk-neutral pricing, we determine the price of a given asset according to its expected payoff:

For example, suppose someone promises to pay you

1,000,000 dollars if “heads” is the outcome of a fair coin flip

0 dollars if “tails” is the outcome

Let’s denote the payoff as \(G\), so that

Suppose in addition that you can sell this promise to anyone who wants it.

First they pay you \(P\), the price at which you sell it

Then they get \(G\), which could be either 1,000,000 or 0.

What’s a fair price for this asset (this promise)?

The definition of “fair” is ambiguous, but we can say that the risk-neutral price is 500,000 dollars.

This is because the risk-neutral price is just the expected payoff of the asset, which is

21.3.2. A comment on risk#

As suggested by the name, the risk-neutral price ignores risk.

To understand this, consider whether you would pay 500,000 dollars for such a promise.

Would you prefer to receive 500,000 for sure or 1,000,000 dollars with 50% probability and nothing with 50% probability?

At least some readers will strictly prefer the first option — although some might prefer the second.

Thinking about this makes us realize that 500,000 is not necessarily the “right” price — or the price that we would see if there was a market for these promises.

Nonetheless, the risk-neutral price is an important benchmark, which economists and financial market participants try to calculate every day.

21.3.3. Discounting#

Another thing we ignored in the previous discussion was time.

In general, receiving \(x\) dollars now is preferable to receiving \(x\) dollars in \(n\) periods (e.g., 10 years).

After all, if we receive \(x\) dollars now, we could put it in the bank at interest rate \(r > 0\) and receive \( (1 + r)^n x \) in \(n\) periods.

Hence future payments need to be discounted when we consider their present value.

We will implement discounting by

multiplying a payment in one period by \(\beta < 1\)

multiplying a payment in \(n\) periods by \(\beta^n\), etc.

The same adjustment needs to be applied to our risk-neutral price for the promise described above.

Thus, if \(G\) is realized in \(n\) periods, then the risk-neutral price is

21.3.4. European call options#

Now let’s price a European call option.

The option is described by three things:

\(n\), the expiry date,

\(K\), the strike price, and

\(S_n\), the price of the underlying asset at date \(n\).

For example, suppose that the underlying is one share in Amazon.

The owner of this option has the right to buy one share in Amazon at price \(K\) after \(n\) days.

If \(S_n > K\), then the owner will exercise the option, buy at \(K\), sell at \(S_n\), and make profit \(S_n - K\).

If \(S_n \leq K\), then the owner will not exercise the option and the payoff is zero.

Thus, the payoff is \(\max\{ S_n - K, 0 \}\).

Under the assumption of risk neutrality, the price of the option is the expected discounted payoff:

Now all we need to do is specify the distribution of \(S_n\), so the expectation can be calculated.

Suppose we know that \(S_n \sim LN(\mu, \sigma)\) and \(\mu\) and \(\sigma\) are known.

If \(S_n^1, \ldots, S_n^M\) are independent draws from this lognormal distribution then, by the law of large numbers,

We suppose that

μ = 1.0

σ = 0.1

K = 1

n = 10

β = 0.95

We set the simulation size to

M = 10_000_000

Here is our code

S = np.exp(μ + σ * np.random.randn(M))

return_draws = np.maximum(S - K, 0)

P = β**n * np.mean(return_draws)

print(f"The Monte Carlo option price is approximately {P:3f}")

The Monte Carlo option price is approximately 1.036982

21.4. Pricing via a dynamic model#

In this exercise we investigate a more realistic model for the share price \(S_n\).

This comes from specifying the underlying dynamics of the share price.

First we specify the dynamics.

Then we’ll compute the price of the option using Monte Carlo.

21.4.1. Simple dynamics#

One simple model for \(\{S_t\}\) is

where

\(S_0\) is lognormally distributed and

\(\{ \xi_t \}\) is IID and standard normal.

Under the stated assumptions, \(S_n\) is lognormally distributed.

To see why, observe that, with \(s_t := \ln S_t\), the price dynamics become

Since \(s_0\) is normal and \(\xi_1\) is normal and IID, we see that \(s_1\) is normally distributed.

Continuing in this way shows that \(s_n\) is normally distributed.

Hence \(S_n = \exp(s_n)\) is lognormal.

21.4.2. Problems with simple dynamics#

The simple dynamic model we studied above is convenient, since we can work out the distribution of \(S_n\).

However, its predictions are counterfactual because, in the real world, volatility (measured by \(\sigma\)) is not stationary.

Instead it rather changes over time, sometimes high (like during the GFC) and sometimes low.

In terms of our model above, this means that \(\sigma\) should not be constant.

21.4.3. More realistic dynamics#

This leads us to study the improved version:

where

Here \(\{\eta_t\}\) is also IID and standard normal.

21.4.4. Default parameters#

For the dynamic model, we adopt the following parameter values.

default_μ = 0.0001

default_ρ = 0.1

default_ν = 0.001

default_S0 = 10

default_h0 = 0

(Here default_S0 is \(S_0\) and default_h0 is \(h_0\).)

For the option we use the following defaults.

default_K = 100

default_n = 10

default_β = 0.95

21.4.5. Visualizations#

With \(s_t := \ln S_t\), the price dynamics become

Here is a function to simulate a path using this equation:

def simulate_asset_price_path(μ=default_μ, S0=default_S0, h0=default_h0, n=default_n, ρ=default_ρ, ν=default_ν):

s = np.empty(n+1)

s[0] = np.log(S0)

h = h0

for t in range(n):

s[t+1] = s[t] + μ + np.exp(h) * randn()

h = ρ * h + ν * randn()

return np.exp(s)

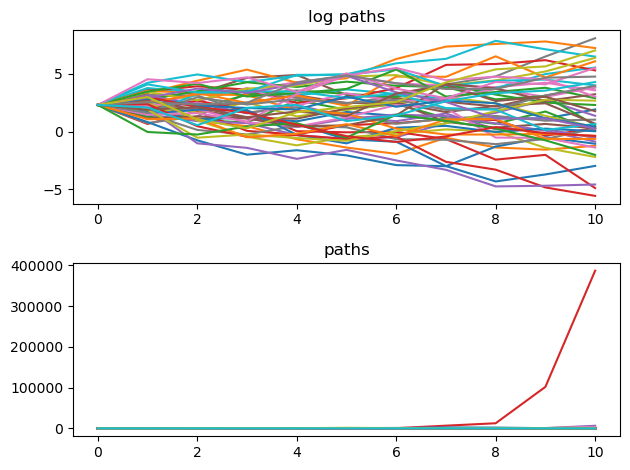

Here we plot the paths and the log of the paths.

21.4.6. Computing the price#

Now that our model is more complicated, we cannot easily determine the distribution of \(S_n\).

So to compute the price \(P\) of the option, we use Monte Carlo.

We average over realizations \(S_n^1, \ldots, S_n^M\) of \(S_n\) and appealing to the law of large numbers:

Here’s a version using Python loops.

def compute_call_price(β=default_β,

μ=default_μ,

S0=default_S0,

h0=default_h0,

K=default_K,

n=default_n,

ρ=default_ρ,

ν=default_ν,

M=10_000):

current_sum = 0.0

# For each sample path

for m in range(M):

s = np.log(S0)

h = h0

# Simulate forward in time

for t in range(n):

s = s + μ + np.exp(h) * randn()

h = ρ * h + ν * randn()

# And add the value max{S_n - K, 0} to current_sum

current_sum += np.maximum(np.exp(s) - K, 0)

return β**n * current_sum / M

%%time

compute_call_price()

CPU times: user 194 ms, sys: 4 μs, total: 194 ms

Wall time: 194 ms

np.float64(616.3012431532786)

21.5. Exercises#

Exercise 21.1

We would like to increase \(M\) in the code above to make the calculation more accurate.

But this is problematic because Python loops are slow.

Your task is to write a faster version of this code using NumPy.

Solution to Exercise 21.1

def compute_call_price_vector(β=default_β,

μ=default_μ,

S0=default_S0,

h0=default_h0,

K=default_K,

n=default_n,

ρ=default_ρ,

ν=default_ν,

M=10_000):

s = np.full(M, np.log(S0))

h = np.full(M, h0)

for t in range(n):

Z = np.random.randn(2, M)

s = s + μ + np.exp(h) * Z[0, :]

h = ρ * h + ν * Z[1, :]

expectation = np.mean(np.maximum(np.exp(s) - K, 0))

return β**n * expectation

%%time

compute_call_price_vector()

CPU times: user 5.7 ms, sys: 0 ns, total: 5.7 ms

Wall time: 5.5 ms

np.float64(591.3625786788868)

Notice that this version is faster than the one using a Python loop.

Now let’s try with larger \(M\) to get a more accurate calculation.

%%time

compute_call_price(M=10_000_000)

CPU times: user 3min 11s, sys: 34 ms, total: 3min 11s

Wall time: 3min 11s

np.float64(844.9603726521862)

Exercise 21.2

Consider that a European call option may be written on an underlying with spot price of $100 and a knockout barrier of $120.

This option behaves in every way like a vanilla European call, except if the spot price ever moves above $120, the option “knocks out” and the contract is null and void.

Note that the option does not reactivate if the spot price falls below $120 again.

Use the dynamics defined in (21.1) to price the European call option.

Solution to Exercise 21.2

default_μ = 0.0001

default_ρ = 0.1

default_ν = 0.001

default_S0 = 10

default_h0 = 0

default_K = 100

default_n = 10

default_β = 0.95

default_bp = 120

def compute_call_price_with_barrier(β=default_β,

μ=default_μ,

S0=default_S0,

h0=default_h0,

K=default_K,

n=default_n,

ρ=default_ρ,

ν=default_ν,

bp=default_bp,

M=50_000):

current_sum = 0.0

# For each sample path

for m in range(M):

s = np.log(S0)

h = h0

payoff = 0

option_is_null = False

# Simulate forward in time

for t in range(n):

s = s + μ + np.exp(h) * randn()

h = ρ * h + ν * randn()

if np.exp(s) > bp:

payoff = 0

option_is_null = True

break

if not option_is_null:

payoff = np.maximum(np.exp(s) - K, 0)

# And add the payoff to current_sum

current_sum += payoff

return β**n * current_sum / M

%time compute_call_price_with_barrier()

CPU times: user 1.14 s, sys: 999 μs, total: 1.14 s

Wall time: 1.14 s

np.float64(0.03792676281101194)

Let’s look at the vectorized version which is faster than using Python loops.

def compute_call_price_with_barrier_vector(β=default_β,

μ=default_μ,

S0=default_S0,

h0=default_h0,

K=default_K,

n=default_n,

ρ=default_ρ,

ν=default_ν,

bp=default_bp,

M=50_000):

s = np.full(M, np.log(S0))

h = np.full(M, h0)

option_is_null = np.full(M, False)

for t in range(n):

Z = np.random.randn(2, M)

s = s + μ + np.exp(h) * Z[0, :]

h = ρ * h + ν * Z[1, :]

# Mark all the options null where S_n > barrier price

option_is_null = np.where(np.exp(s) > bp, True, option_is_null)

# mark payoff as 0 in the indices where options are null

payoff = np.where(option_is_null, 0, np.maximum(np.exp(s) - K, 0))

expectation = np.mean(payoff)

return β**n * expectation

%time compute_call_price_with_barrier_vector()

CPU times: user 28.8 ms, sys: 0 ns, total: 28.8 ms

Wall time: 28.6 ms

np.float64(0.03854578034388481)