24. Dynamics in One Dimension#

24.1. Overview#

In economics many variables depend on their past values

For example, it seems reasonable to believe that inflation last year with affects inflation this year.

(Perhaps high inflation last year will lead people to demand higher wages to compensate, which will feed into higher prices this year.)

Letting \(\pi_t\) be inflation this year and \(\pi_{t-1}\) be inflation last year, we can write this relationship in a general form as

where \(f\) is some function describing the relationship between the variables.

This equation is an example of one-dimensional discrete time dynamic system.

In this lecture we cover the foundations of one-dimensional discrete time dynamics.

(While most quantitative models have two or more state variables, the one-dimensional setting is a good place to learn foundations and understand key concepts.)

Let’s start with some standard imports:

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

24.2. Some definitions#

This section sets out the objects of interest and the kinds of properties we study.

24.2.1. Composition of functions#

For this lecture you should know the following.

If

\(g\) is a function from \(A\) to \(B\) and

\(f\) is a function from \(B\) to \(C\),

then the composition \(f \circ g\) of \(f\) and \(g\) is defined by

For example, if

\(A=B=C=\mathbb R\), the set of real numbers,

\(g(x)=x^2\) and \(f(x)=\sqrt{x}\), then \((f \circ g)(x) = \sqrt{x^2} = |x|\).

If \(f\) is a function from \(A\) to itself, then \(f^2\) is the composition of \(f\) with itself.

For example, if \(A = (0, \infty)\), the set of positive numbers, and \(f(x) = \sqrt{x}\), then

Similarly, if \(n\) is a positive integer, then \(f^n\) is \(n\) compositions of \(f\) with itself.

In the example above, \(f^n(x) = x^{1/(2^n)}\).

24.2.2. Dynamic systems#

A (discrete time) dynamic system is a set \(S\) and a function \(g\) that sends set \(S\) back into to itself.

Examples of dynamic systems include

\(S = (0, 1)\) and \(g(x) = \sqrt{x}\)

\(S = (0, 1)\) and \(g(x) = x^2\)

\(S = \mathbb Z\) (the integers) and \(g(x) = 2 x\)

On the other hand, if \(S = (-1, 1)\) and \(g(x) = x+1\), then \(S\) and \(g\) do not form a dynamic system, since \(g(1) = 2\).

\(g\) does not always send points in \(S\) back into \(S\).

We care about dynamic systems because we can use them to study dynamics!

Given a dynamic system consisting of set \(S\) and function \(g\), we can create a sequence \(\{x_t\}\) of points in \(S\) by setting

This means that we choose some number \(x_0\) in \(S\) and then take

This sequence \(\{x_t\}\) is called the trajectory of \(x_0\) under \(g\).

In this setting, \(S\) is called the state space and \(x_t\) is called the state variable.

Recalling that \(g^n\) is the \(n\) compositions of \(g\) with itself, we can write the trajectory more simply as

In all of what follows, we are going to assume that \(S\) is a subset of \(\mathbb R\), the real numbers.

Equation (24.1) is sometimes called a first order difference equation

first order means dependence on only one lag (i.e., earlier states such as \(x_{t-1}\) do not enter into (24.1)).

24.2.3. Example: a linear model#

One simple example of a dynamic system is when \(S=\mathbb R\) and \(g(x)=ax + b\), where \(a, b\) are constants (sometimes called ``parameters’’).

This leads to the linear difference equation

The trajectory of \(x_0\) is

Continuing in this way, and using our knowledge of geometric series, we find that, for any \(t = 0, 1, 2, \ldots\),

We have an exact expression for \(x_t\) for all non-negative integer \(t\) and hence a full understanding of the dynamics.

Notice in particular that \(|a| < 1\), then, by (24.4), we have

regardless of \(x_0\).

This is an example of what is called global stability, a topic we return to below.

24.2.4. Example: a nonlinear model#

In the linear example above, we obtained an exact analytical expression for \(x_t\) in terms of arbitrary non-negative integer \(t\) and \(x_0\).

This made analysis of dynamics very easy.

When models are nonlinear, however, the situation can be quite different.

For example, in a later lecture The Solow-Swan Growth Model, we will study the Solow-Swan growth model, which has dynamics

Here \(k=K/L\) is the per capita capital stock, \(s\) is the saving rate, \(A\) is the total factor productivity, \(\alpha\) is the capital share, and \(\delta\) is the depreciation rate.

All these parameter are positive and \(0 < \alpha, \delta < 1\).

If you try to iterate like we did in (24.3), you will find that the algebra gets messy quickly.

Analyzing the dynamics of this model requires a different method (see below).

24.3. Stability#

Consider a dynamic system consisting of set \(S \subset \mathbb R\) and \(g\) mapping \(S\) to \(S\).

24.3.1. Steady states#

A steady state of this system is a point \(x^*\) in \(S\) such that \(x^* = g(x^*)\).

In other words, \(x^*\) is a fixed point of the function \(g\) in \(S\).

For example, for the linear model \(x_{t+1} = a x_t + b\), you can use the definition to check that

\(x^* := b/(1-a)\) is a steady state whenever \(a \not= 1\),

if \(a = 1\) and \(b=0\), then every \(x \in \mathbb R\) is a steady state,

if \(a = 1\) and \(b \not= 0\), then the linear model has no steady state in \(\mathbb R\).

24.3.2. Global stability#

A steady state \(x^*\) of the dynamic system is called globally stable if, for all \(x_0 \in S\),

For example, in the linear model \(x_{t+1} = a x_t + b\) with \(a \not= 1\), the steady state \(x^*\)

is globally stable if \(|a| < 1\) and

fails to be globally stable otherwise.

This follows directly from (24.4).

24.3.3. Local stability#

A steady state \(x^*\) of the dynamic system is called locally stable if there exists an \(\epsilon > 0\) such that

Obviously every globally stable steady state is also locally stable.

Here is an example where the converse is not true.

Example 24.1

Consider the self-map \(g\) on \(\mathbb{R}\) defined by \(g(x)=x^2\). The fixed point \(1\) is not stable.

For example, \(g^t (x)\to\infty\) for any \(x>1\).

However, \(0\) is locally stable, because \(-1<x<1\) implies that \(g^t (x)\to 0\) as \(t\to\infty\).

Since we have more than one fixed point, \(0\) is not globally stable.

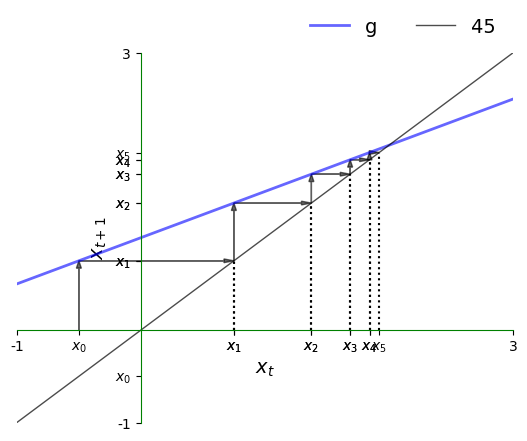

24.4. Graphical analysis#

As we saw above, analyzing the dynamics for nonlinear models is nontrivial.

There is no single way to tackle all nonlinear models.

However, there is one technique for one-dimensional models that provides a great deal of intuition.

This is a graphical approach based on 45-degree diagrams.

Let’s look at an example: the Solow-Swan model with dynamics given in (24.6).

We begin with some plotting code that you can ignore at first reading.

The function of the code is to produce 45-degree diagrams and time series plots.

Let’s create a 45-degree diagram for the Solow-Swan model with a fixed set of parameters. Here’s the update function corresponding to the model.

def g(k, A = 2, s = 0.3, alpha = 0.3, delta = 0.4):

return A * s * k**alpha + (1 - delta) * k

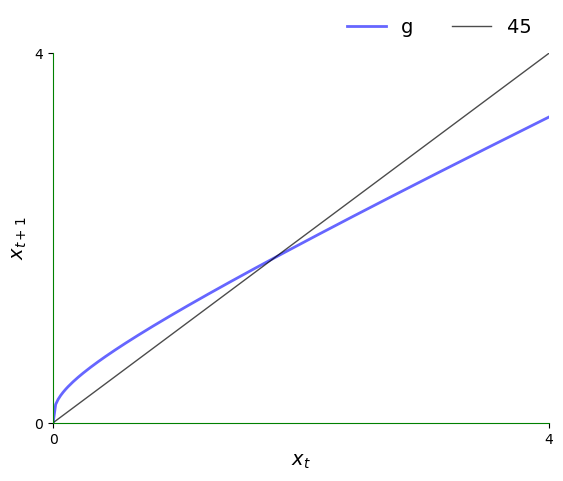

Here is the 45-degree plot.

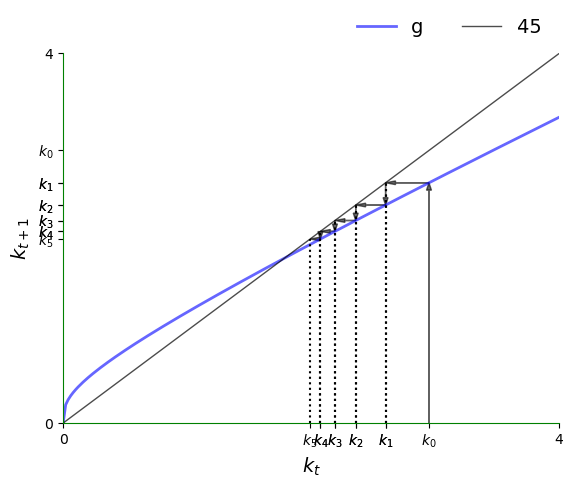

The plot shows the function \(g\) and the 45-degree line.

Think of \(k_t\) as a value on the horizontal axis.

To calculate \(k_{t+1}\), we can use the graph of \(g\) to see its value on the vertical axis.

Clearly,

If \(g\) lies above the 45-degree line at this point, then we have \(k_{t+1} > k_t\).

If \(g\) lies below the 45-degree line at this point, then we have \(k_{t+1} < k_t\).

If \(g\) hits the 45-degree line at this point, then we have \(k_{t+1} = k_t\), so \(k_t\) is a steady state.

For the Solow-Swan model, there are two steady states when \(S = \mathbb R_+ = [0, \infty)\).

the origin \(k=0\)

the unique positive number such that \(k = s z k^{\alpha} + (1 - \delta) k\).

By using some algebra, we can show that in the second case, the steady state is

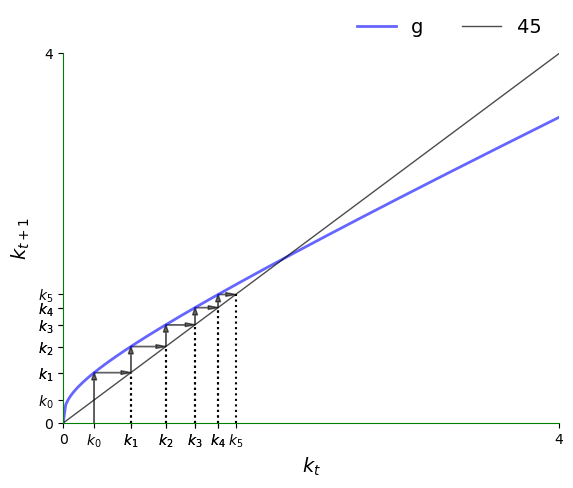

24.4.1. Trajectories#

By the preceding discussion, in regions where \(g\) lies above the 45-degree line, we know that the trajectory is increasing.

The next figure traces out a trajectory in such a region so we can see this more clearly.

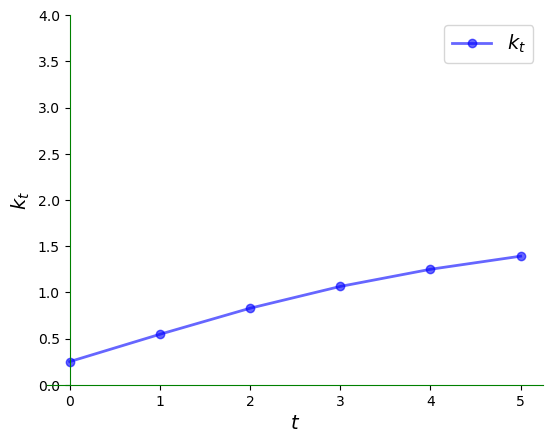

The initial condition is \(k_0 = 0.25\).

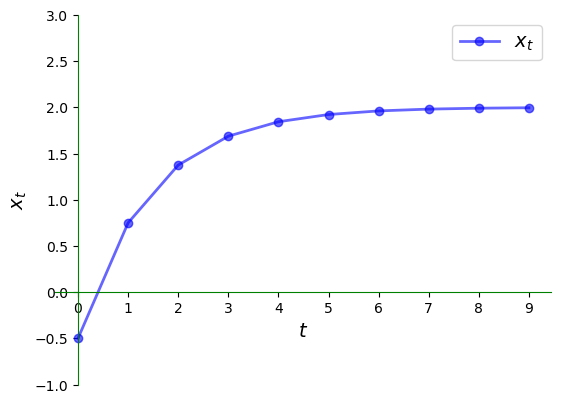

We can plot the time series of per capita capital corresponding to the figure above as follows:

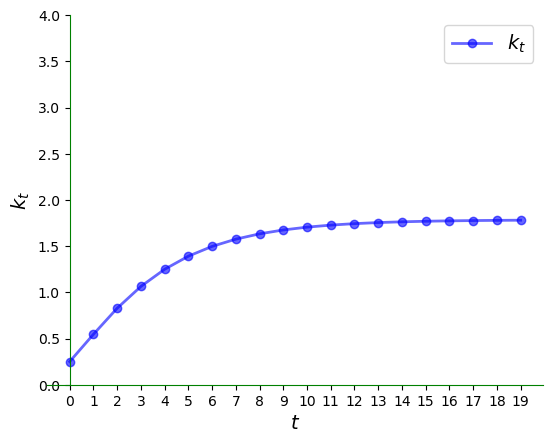

Here’s a somewhat longer view:

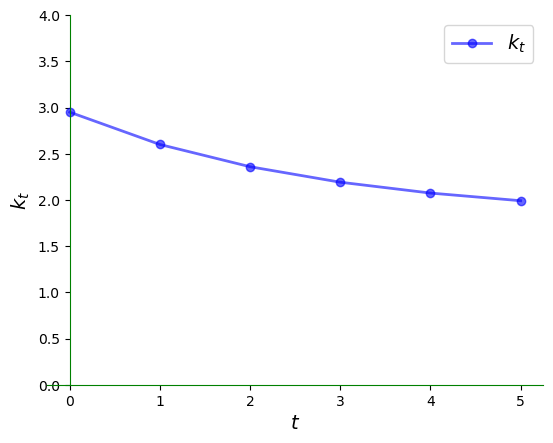

When per capita capital stock is higher than the unique positive steady state, we see that it declines:

Here is the time series:

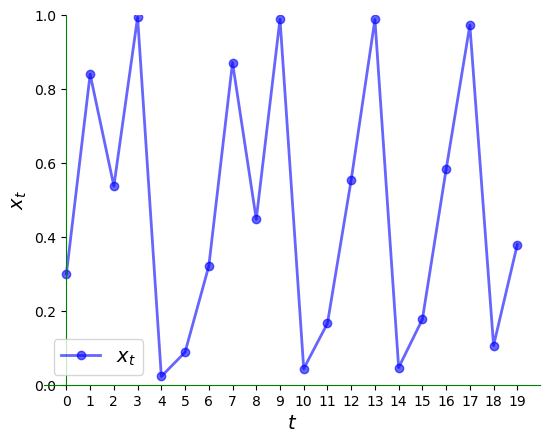

24.4.2. Complex dynamics#

The Solow-Swan model is nonlinear but still generates very regular dynamics.

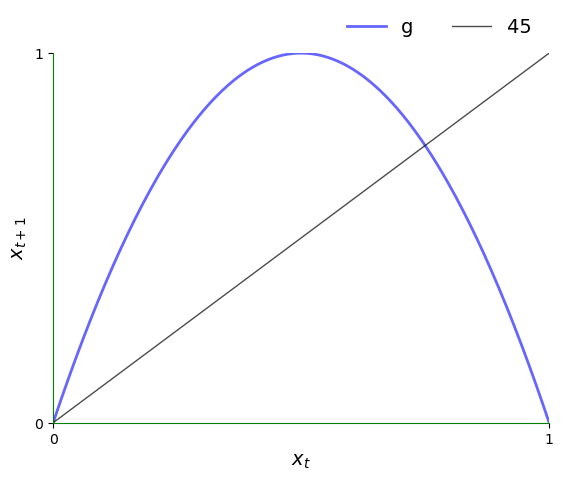

One model that generates irregular dynamics is the quadratic map

Let’s have a look at the 45-degree diagram.

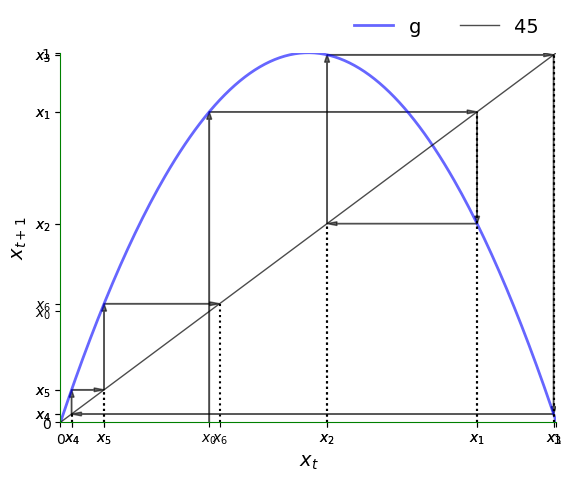

Now let’s look at a typical trajectory.

Notice how irregular it is.

Here is the corresponding time series plot.

The irregularity is even clearer over a longer time horizon:

24.5. Exercises#

Exercise 24.1

Consider again the linear model \(x_{t+1} = a x_t + b\) with \(a \not=1\).

The unique steady state is \(b / (1 - a)\).

The steady state is globally stable if \(|a| < 1\).

Try to illustrate this graphically by looking at a range of initial conditions.

What differences do you notice in the cases \(a \in (-1, 0)\) and \(a \in (0, 1)\)?

Use \(a=0.5\) and then \(a=-0.5\) and study the trajectories.

Set \(b=1\) throughout.

Solution to Exercise 24.1

We will start with the case \(a=0.5\).

Let’s set up the model and plotting region:

a, b = 0.5, 1

xmin, xmax = -1, 3

g = lambda x: a * x + b

Now let’s plot a trajectory:

Here is the corresponding time series, which converges towards the steady state.

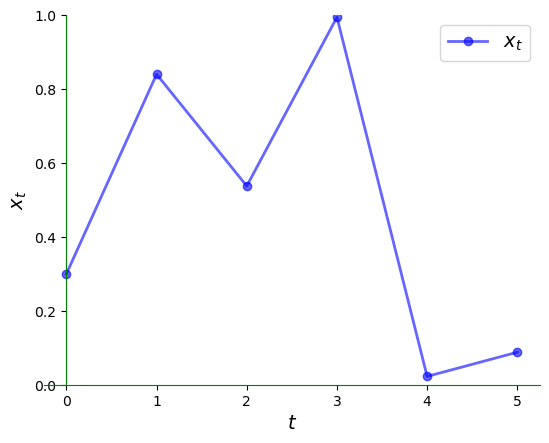

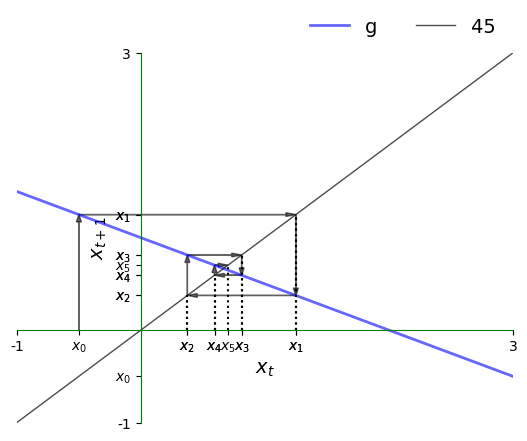

Now let’s try \(a=-0.5\) and see what differences we observe.

Let’s set up the model and plotting region:

a, b = -0.5, 1

xmin, xmax = -1, 3

g = lambda x: a * x + b

Now let’s plot a trajectory:

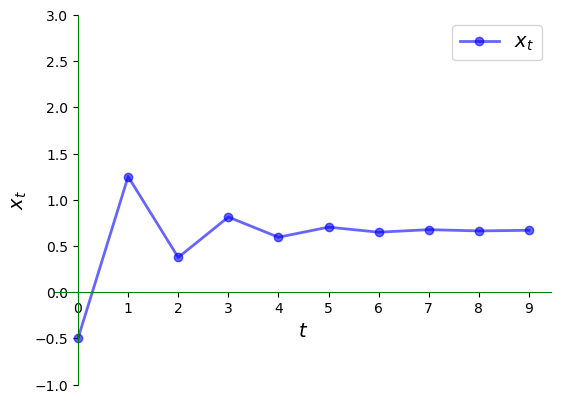

Here is the corresponding time series, which converges towards the steady state.

Once again, we have convergence to the steady state but the nature of convergence differs.

In particular, the time series jumps from above the steady state to below it and back again.

In the current context, the series is said to exhibit damped oscillations.